Discover Authentic Parsi Food in Ahmedabad at The Bawa Bistro!

Ever since the heyday of the docks at Lothal by the banks of the Indus thousands of years ago, the western Indian state of Gujarat has been at the centre of scores of trade routes connecting it to the worlds on the other side of the Arabian Sea. The interactions that stemmed out of these connections led to innumerable migrations over the centuries, often riddled with complex histories of violence and oppression, such as the numerous indentured labourers that were transported to other colonies by the Brits, or the thousands of East Africans that were brought here as slaves by the Arabs, Portuguese and other empires, some of whom still stay here and are known as the Siddis. Yet, the legacy of such migrations endure, whether it be the Siddi Saiyyed ni Masjid, built by an African slave-turned-nobleman in 1511, or the numerous homes in Old Ahmedabad that are decorated with Teak Wood from Burma (Myanmar) courtesy the several trade routes established during the colonial period.

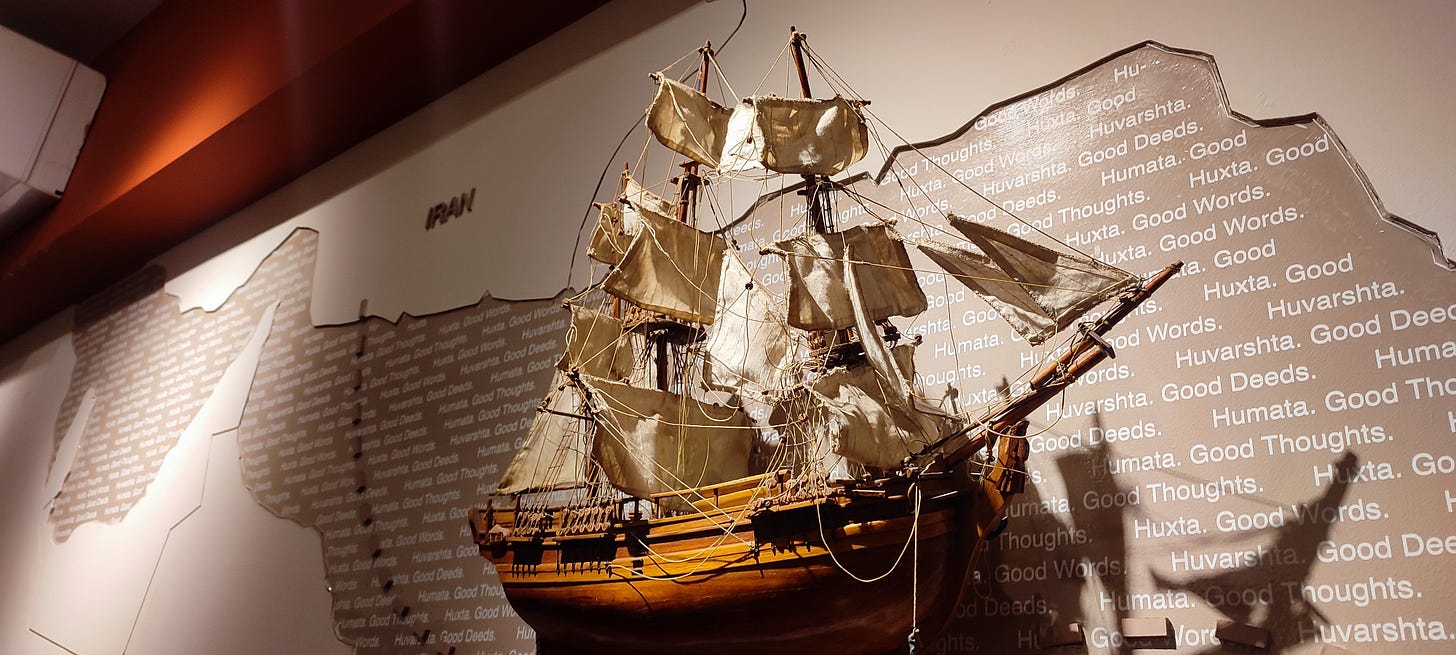

One such group is the Parsis - the group of Zoroastrians that arrived in India around 1000 years ago, fleeing religious persecution that started in the 7th century with the emergence and spread of Islam. Not much remains of the history of journey, except for a late 16th century text known as the Qissa-i-Sanjan (Story of Sanjan), written around six centuries after their first estimated date of arrival. Per this text, this group of Zoroastrians were originally inhabitants of Persia, residing in Greater Khorasan, and fled to a major port city by the Arabian Sea following religious persecution after the fall of the Sassanids. From there, they set sail for the island of Diu on the Kathiawar Peninsula, and eventually ended up settling in southern Gujarat and establishing the settlement of Sanjan after being granted asylum by the local king, on the conditions that they adopt the local language and assimilate to the local culture. The Parsis eventually settled in various towns across Gujarat, such as Valsad, Navsari and Udvada, the latter of which continues to host the oldest fire temple of India, and have been an inseparable part of Gujarati culture ever since.

Bawa Bistro in Navrangpura pays homage to the Parsi heritage of Gujarat. This small haunt was founded by Tiraz Commessariat, a Parsi himself, around a year ago, and has quickly become one of my most-loved restaurants in Ahmedabad. I’ve had around a third of their menu and every single dish of theirs is a flawless banger, and is a perfect representation of authentic Parsi food that everyone must try.

Their Russian Cutlets are extremely light-weight, they’re fried but do not come across as oily, and contain a wonderfully crispy coating that contrasts extremely well with the soft, gooey and cheesy filling.

Their Chicken Farchas, a traditional Parsi take on the fried chicken, are so wonderfully golden you could mistake them for a Padma Bhushan medal, and I’m going to be honest, this dish probably deserves one. The chicken is extremely tender, the coating of breadcrumbs gives it a slightly grainy texture, and is only mildly flavoured with basic masalas, which allows the beautiful cuts of meat to shine. It is served with a viscous cheesy dip which goes decently with the chicken, but can be avoided too.

Dhansak is a traditional slow-cooked Parsi dish which is usually only prepared on Sundays owing to its long preparation time. It is a stew of mutton, lentils and vegetables, which is slow-cooked over the course of several hours, and served with caramelised rice topped with some small meatballs or kebabs. The Dhansak at Bawa Bistro was incredibly mellow, the mix of the flavours of the meat and lentils coming through the gravy, and the pieces of mutton were as tender as cotton candy, almost immediately melting in your mouth.

Their Patra ni Macchi is prepared by coating fillets of freshly sourced Black Pomfret (they can prepare it with White Pomfret instead if you inform them a day prior) with a mixture of coconut chutney, coriander chutney, and lemon. The fish is then wrapped in banana leaves and steamed until ready. The final product is an incredibly tender fish that breaks apart on touch, covered in a tangy, coconut-y mixture that kept recurring in my dreams for days on end. This is perhaps the best thing that they serve here and I am incredibly grateful to not be allergic to seafood.

Their Kheema Pav is an ode to the various Irani Cafes of Bombay, where the dish is said to have been invented. Their Kheema is finely ground, and you can taste the flavours of the coriander, black pepper, cumin and other masalas that give it a strong, rich, mellow flavour that is best with their fluffy pavs.

For vegetarian main courses, I recommend Khursheed’s Badami Paneer, cubes of cottage cheese served in a creamy almond gravy, and the Sali Papetti, the vegetarian counterpart of the Sali Boti, which has soft and savoury vegetarian kebabs in a tomato-based gravy topped with Sali, or, crunchy potato strips similar to many Gujarati farsans.

For dessert, try their Caramel Custard, which is the appropriate amount of sweet, incredibly bouncy and soft, or, you could try their Lagan Nu Custard, a baked dessert traditionally served at Parsi weddings, that is just as soft but is topped with assorted dry fruits and gets its underlying flavour from there, not from the sugary caramel of the former. Honestly, their desserts are so good it may as well be worth it to come here just for them.

Finally, don’t forget to order Pallonji’s Sodas, a staple at many Bombay Irani Cafes, to douse the food down with. Honestly, all of them are incredible and unique in their own ways, but I recommend Raspberry and Ice-Cream Soda in particular. The sweet, tarty, and fizzy raspberry soda has virtually become an emblem of Parsi food, ever since Pallonji’s started their soda operations in Bombay in 1865. The Ice Cream Soda tastes like a mixture between a coke float in a bottle and fennel seeds. It is perhaps the most unique soda I have tasted in my 22 years of professional soda drinking career and I keep craving for a bottle every time I sit for dinner.

The impacts of migration from Iran, and assimilation into Gujarati culture, is visible in the cuisine of the Parsis. Patra ni Macchi borrows from Gujarati-style Patra – steamed colocasia leaves coated with spiced besan and topped with coconut. It may be the case that the slow-cooking of the lentils and meat for the Dhansak was a tradition carried over from Persia, but over time, the dish adopted spices commonly available in Gujarat. Parsi cuisine is an incredibly unique, beautiful and flavourful one, and I’m glad that institutions such as The Bawa Bistro continue to keep the cuisine’s legacy alive.

Recommendations:

Chicken Farcha (9.5/10), Russian Cutlets (9.5/10), Patra Ni Macchi (9.75/10), Mutton Kheema Pav (9.25/10), Mutton Dhansak (9.5/10), Lagan nu Custard (9.75/10), Caramel Custard (9.75/10), Sali Papeti (9/10), Khursheed’s Badami Paneer (8/10)

Strongly recommend grabbing a Pallonji’s Soda, preferably Raspberry or Ice Cream, as well.