Spending 3 days in Banaras: A Weekend in the City of Light, Part 1

A month ago, an inescapable urge to witness the eternal flow of one of India's most majestic rivers - the Ganga - had overrun every sense of my being. I felt an invisible force pulling myself towards the banks of the mighty river, and soon started to look for opportunities to run away to a city where I could witness her glory in its entirety. Kanpur? Too boring. Allahabad? Too crowded. Ultimately, my mind settled on the city that has long been most associated with the holy river, and the one that also had the most options to spend a whole weekend - the city of Banaras, known by countless names, to some it is Kashi, to others it is Avimukta, Rudravasa, Varanasi, or Mahashmashana, to many it is all at once. So, on a long weekend that happened to be in this fine April, I packed my bags, booked a small room by the Dashashwamedh Ghat, hopped on a train and found myself in a place I have never been to before - the City of Light.

Upon disembarking from my train on a fine Friday morning, I hustled through the autowallahs at the railway station, found a shared ride that would take me towards my destination, walked through the massive plaza of the bazaar at Godowlia, and found myself standing at the grand Dashashwamedh Ghat - the chief Ghat that planks the shores of the mighty Ganga, named after the Ashwamedh Yajna (religious ceremony involving sacrifice of horses) involving ten (das in Hindi and dasham in Sanskrit) horses that Brahma, the creator God in Hindu mythology, held here, to be able to have a darshan (lit. "to view", but is used in a religious sense in Hinduism vis-a-vis idol worship) of Lord Shiva and his linga, as narrated in the Kashi Kedara Mahatmaya. The morning breeze was strong, cool, and pleasant, and the Ghat was overrun with pilgrims and tourists like me, some bathing in the holy river's waters, others sipping lemon tea while seated on the steps. Some strolled towards the centerpiece of Kashi - the Vishwanath temple just a few ghats away, others involved in poojas and other religious ceremonies.

While my primary motivation to visit the city was to see the mighty Ganga for the first time in my life, the desire to witness one of India's most prominent cultural centers was also pretty strong. At the time, I was half-way through reading Diana L. Eck's classic "Banaras: A City of Light", a religious and cultural history of the holy city that references the vast corpus of Hindu mythology to wonderfully map out Varanasi's geography and explain the lore behind its cultural sites. Now, I am not a religious man in any sense of the word; if anything I am a radical opposite of it, but to discount the cultural and historic importance Kashi has in India is fool's play. Varanasiis said to be a microcosm of Hindu culture - something it takes quite literally by way of having temples and religious sites dedicated to almost every major deity within its boundaries, whether it be the Linga at Kedarnath represented in Kedar Khand, the city of Ayodhya represented in the Ram Kund on Luxa Road, the Holy Dham of Haridvar present at Asi Ghat, or the Sangam at Prayag being present at the Panchaganga Ghat – Kashi is all-encompassing, and if its mythologies are to believed, it is as much a part of India, as the entirety of India is a part of it.

For centuries, visitors have been spell-struck by the religiosity and spirituality emanating from this city. famously described by Mark Twain as “older than history, older than tradition, older even than legend” - a cultural landmark on any atlas you can get your hands on, a city without which the idea of India in its present form is perhaps impossible to even think of, a city that has captured the spiritual imaginations of over a billion Hindus, and perhaps even more admirers. Surely, there is something to explore here. Surely, there is something to be fascinated by.

Unfortunately, my first, and lasting impression of the city was one full of disappointment. The area once known as Anandvana (lit. Forest of Bliss), a calm, serene forest full with hundreds of shivalings, south of the then-city centre at Rajghat, and now comprising modern-day Banaras, has been long lost to history, and what remains after around a century of haphazard modern urban planning is a densely packed city marked by small homes, narrow gullies and open wiring. What was once a quiet jungle well-suited to spiritual practice is now a filthy city lacking even bare minimum sanitation, and if one were unaware of the history of this place, they would never mistake it as having been India's most prominent spiritual center over the past 4 millenia. I have extensively explored many cities with densely packed old towns infamous for their narrow gullies, from Ahmedabad to Delhi to Lucknow, and these areas are often neglected by local administrations, with terrible drainage systems, sub-par cleanliness, and little to no accountability from the municipalities. Varanasi may be dirtier and smellier than all of these cities combined. Most gullies I roamed through, even those not having large tourist footfalls, have massive open gutters, are littered with animal excreta, and have barely any cleanliness, leading to vast stretches of the city smelling like a putrid, disgusting mixture of dung and sewer waste.

It is difficult to see one of India's most important historic and cultural centres in this pathetic state of being. You would imagine that a party that rose to global prominence on the bank of an ideology best described as Hindu Nationalism, and whose leader in Parliament successfully contested elections from the city THRICE, would care more about the condition of basic amenities in the most holiest city in Hinduism, one that is unmistakably part of the holiest cities of the world. Despite all the political patronage it has received since 2014, it will be a long, long time before Kashi truly becomes Kyoto, and at this rate, it is more realistic to aim to reach the levels of Kurukshetra or Kolhapur, and even that would take a couple decades.

For anyone even slightly familiar with Indian history and architecture, Mark Twain’s quote of Banaras being “older than history” itself falls flat on the first glance of the city itself. The city’s architecture is not ancient by any stretch of the word. Most forts, ghats, and even several temples were constructed in the medieval era, as a result of Maratha and Mughal patronage under Akbar, starting from the late 16th century onwards, as reactions to the city being ransacked by multiple Islamic kingdoms. The narrow gullies that define the city centre of Kashi are, as described earlier, the misfortune of the past 100 or 150 years of urban planning, starting with the British, and continuing undeterred post-independence. The various lakes and streams that used to mark the city of old are nowhere to be found; and today merely comprise small kunds (ponds) and nalas (gutters). Of course, the traditions and religious sites of the city are unmistakably prehistoric, which is probably what Mark Twain’s quote referred to in the first place. I’m just annoyed about people proclaiming it to be a city where stepping foot in makes you feel like you’re in a place that is older than history itself. Anyone who is even remotely familiar with mediaeval Indian architecture would not be mistaken for present-day Varanasi’s true age.

And finally, the major reason why the city is frequented so much - the temple of Vishwanath, Lord of the World, known as being the most pre-eminent of the hundreds (and possibly thousands) of Shiva temples that have graced Kashi over the years. The temple management here was not disappointing, although I would recommend you to visit the temple as early as possible if you do not wish to spend hours waiting in line. I visited the temple at 6 am and had to wait for around half an hour before I could have darshan of the idol, which lasted for little more than three-quarters of a second before the security-wallahs pushed me out of the line. A worse experience was to be had at the Kaal Bhairav Temple, another historic idol of Shiva considered to be the kotwal (watchman) of the city. Hindu mythology believes that everyone wanting to stay in the city must take permission from Kaal Bhairav, and it is often considered ideal to visit this temple before that of Vishwanath, for similar reasons. Unfortunately, the management here is utterly chaotic. There is little to no clarity over entry and exit gates, and there seems to be much confusion over where shoes are to be taken off before entering the temple, leading to me having to stand in line thrice at prime darshan time (once to deposit my shoes, once more for the darshan, and one last time to collect my shoes), again, for merely a second of a glimpse of the idol of Kaal Bhairav that I do not even recollect.

Though, not all temples are as crowded and mismanaged as these two are. The Nepali Temple, constructed by the Maharajadhiraja of Nepal during his exile to the city in the early 19th century, situated upon a hill at Lalita Ghat is mostly quiet. It oversees a small compound, where you can sit under the shade of some Peepal trees and have a bird’s eye view of the mighty Ganga. This was one of the only temples I felt at peace in my trip here, an oasis of serenity in a city that does not have space to breathe in. Two other temples I visited, were the Vishalakshi Mata Shakti Peeth and Maa Sankata Devi Temple, extremely important temples in the Hindu fold. The former is one of 51 Shakti Peethas, which are believed to be the places where pieces of Sati’s body fell after her demise at the hands of Vishnu, and the site of the Vishalakshi temple is considered to be where her earrings fell. The latter, one of the original Matrikas - goddesses of Puranic folk traditions that were not associated with male deities, although over the years and with eventual assimilation into the larger Hindu fold, she has been identified with Shiva’s consort, Bhavani, slayer of Mahishasura and a multiform of Shiva. There are hundreds of other temples scattered across the city, but unfortunately I did not have the time or the energy to make a pilgrimage to them in scorching April heat.

What was unmistakably the most enjoyable part of the trip was the Ghats of Banaras, even as the levels of the Ganga were not as high as I hoped them to be, and the grandeur of the Ganga which I went to witness being largely unfulfilled due to the time of year I chose to visit it. The Ghats of Benaras stand in great contrast to the cities that lie within its borders. The flights of steps that descend from the hilltops and forts above the horizon leave ample space for pilgrims to walk, for children to play cricket, for students to study the Vedas, for hustlers to sell their goods to tourists, and for devotees to pray or engage in religious rituals. The eastward border of Banaras along the river remains one part of the city which retains its spiritual connection to nature - and merely sitting by the Ghats, observing the activity of the city and relishing the cool breeze of the Ganga was enough to redeem the parts of the city.

Banaras has, amongst its eastward border, 84 ghats, starting from Assi Ghat in the South, on the northward end of the seasonal Assi river, and ending at the Adi Keshava Ghat, on the southward border of the Varuna river. Traditionally, this has been considered to be the zone encompassing Varanasi - and the etymology of the city is popularly considered to be derived from the two rivers (Varuna + Assi = Varanasi), although Diana L. Eck disputes this in her book mentioned above, proposing instead that the Varuna was earlier known as the Varanasi river, from which the city derived its name, and the Assi is no more than a “dried up rivulet”, which would only resemble a river in the monsoon.

If you’re enjoying reading this post, subscribe to my newsletter for FREE to receive WEEKLY food and travel musings from Uttar Pradesh, Delhi, Ahmedabad and beyond!

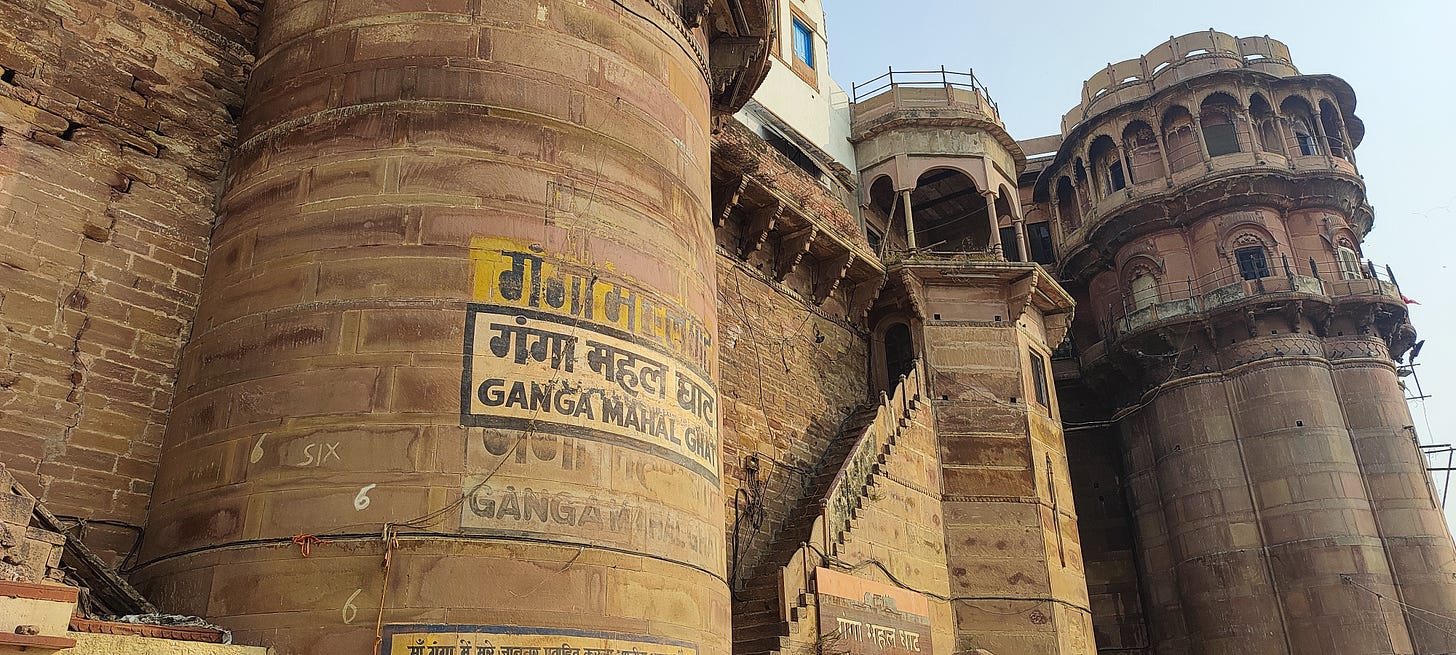

One thing I would recommend every visitor to do, would be to stroll across the various Ghats of Banaras, for there is something to do and something to see alongside all of them. On my last day, I walked from the Assi Ghat all the way in the south to the Hanumanagardh Ghat (roughly the 73rd Ghat out of 84), even far northward of Vishwanath. Various medieval-era forts and palaces can be seen on this expedition. There are the palaces at Ganga Mahal Ghat, Man Mandir Ghat and Darbhanga Ghat, the fortifications at Chet Singh Ghat, Rana Mahal Ghat, Bhonsale Ghat, Jalasen Ghat, and many more.

Other Ghats have their own historical quirks as well. The Jantar Mantar of Varanasi is located on top of the palace at Man Mandir Ghat, which has now been converted to a Virtual Experiential Museum consisting of exhibitions on the culture and heritage of Varanasi. The Tulsi Ghat was home to the poet Tulsidas, who wrote the Ramcharitmanas, his version of the epic poem Ramayana in vernacular Awadhi. The Panchaganga Ghat, where the Alamgir Mosque constructed by Aurangzeb stands, is revered as the confluence of five sacred rivers - the Ganga, Yamuna, Saraswati, Dhutpapa and Kirana, hence being called the Panchaganga (lit. five rivers).

Most interestingly, the eternal pyres at Manikarnika and Harishchandra Ghats - considered to be the two most holiest cremation grounds in Hinduism. After all, Varanasi is also called the Mahashmashana - the mega cremation ground. While other cities would traditionally have the cremation ground on the southward outskirts of the city, due to associations of death and cremation with ritual impurity - Varanasi is the only one where the cremation ground is a part of the city centre, Manikarnika being adjacent to the Dashashwamedh Ghat that hosts the temple of Vishwanath.

I earlier noted how Varanasi is literally a microcosm of India itself; every prominent linga, mandir and dham of Hinduism is said to be found in Varanasi as well. You do not need to venture inwards to realise that. A mere glimpse at the names of the rulers that patronised the constructions on the Ghats of the city - from Udaipur to Darbhanga to Ramnagar to Indore - is enough to realise the ritual significance this place holds for the subcontinent.

There are three other things you must do on the Ghats of Banaras.

Firstly, the Ganga Aartis at Dashashwamedh and Assi Ghat, where rituals local priests perform pooja to the holy river Ganga during sunset (Dashashwamedh) and sunrise (Assi). These elaborate, overstimulating yet elegant rituals using snake-headed lamps, rose petals, smoke of incense sticks, the sound of conch shells and peacock feathers are truly glorious to witness, and can be attended for free, from behind the priests, although they do have paid seating more closer to the ritual spot. The Morning Aarti at Assi Ghat is considerably less crowded, and I would recommend you stand at the bottom of the steps of the Ghats, to have a front-on view of the aarti. The evening aarti at Dashashwamedh, much more grander and much more popular, gets quite crowded with there being limited seating available, and I would recommend you to reach there at least an hour before the start of the Aarti to grab a seat for yourselves.

Secondly, you can hop on a boat, with the boatmen giving you a tour of the Ghats from the Ganga. There are several options available, some ferrying you from Assi to Dashashwamedh, others taking you as far as the newly constructed Namo Ghat. What I would recommend you to do is to take a shared boat tour during the evening aarti at Dashashwamedh, who will not only give you a tour of around half of the 84-odd Ghats of Banaras, but also allow you to view the aarti from the boat itself, allowing you to enjoy a front-on view of the festivities that is, quite frankly, a much superior way to witness it than from behind. The standard fare in April ‘25 was 200/- per person for both activities in the smaller boat, and if you’re their first customer of the night, you can negotiate down to around 150/- (which is what I did).

The third activity to be done at the Ghats is to take a boat to the Fort at Ramnagar, the residence of the former ruling dynasty of Benaras, and it still houses a king - the so-called Maharaja of Benaras, self-styled Kashi Naresh Anant Narayan Singh, although that title means nothing in a modern republic, his worth being constitutionally no more or no less than a pauper like me or you.

Spoilers - I did not actually undertake this activity, choosing to visit the Fort via its regular entrance after taking an auto across the Shastri Bridge, which I ended up largely regretting. The area where tourists are permitted to enter inside the Fort premises is mostly limited to the museum showcasing the belongings and weapons of the former royal family - quite frankly a disappointing collection, not well-maintained or well-cleaned either. The grand facade of the Fort, which may be its main attraction, is not visible to those who choose to visit it from inside either, and it would be a better option to ask boatwallahs to ferry you to the banks of the Fort if you are interested in passing some time there (I do not have any experience with booking such a tour myself, but I would guess that boats should be available from Assi Ghat, it being the closest major Ghat to the Fort).

For those interested in history, mythology, and culture, I would recommend you to check out the Bharat Kala Bhavan museum in the Banaras Hindu University campus - which has a wonderful collection, ranging from artefacts of the Indus Valley Civilisation to paintings from a hundred years ago. The ticket is minimal, and photography in the premises is prohibited, although several students of the university can be seen practising their drawing skills while using the sculptures as references.

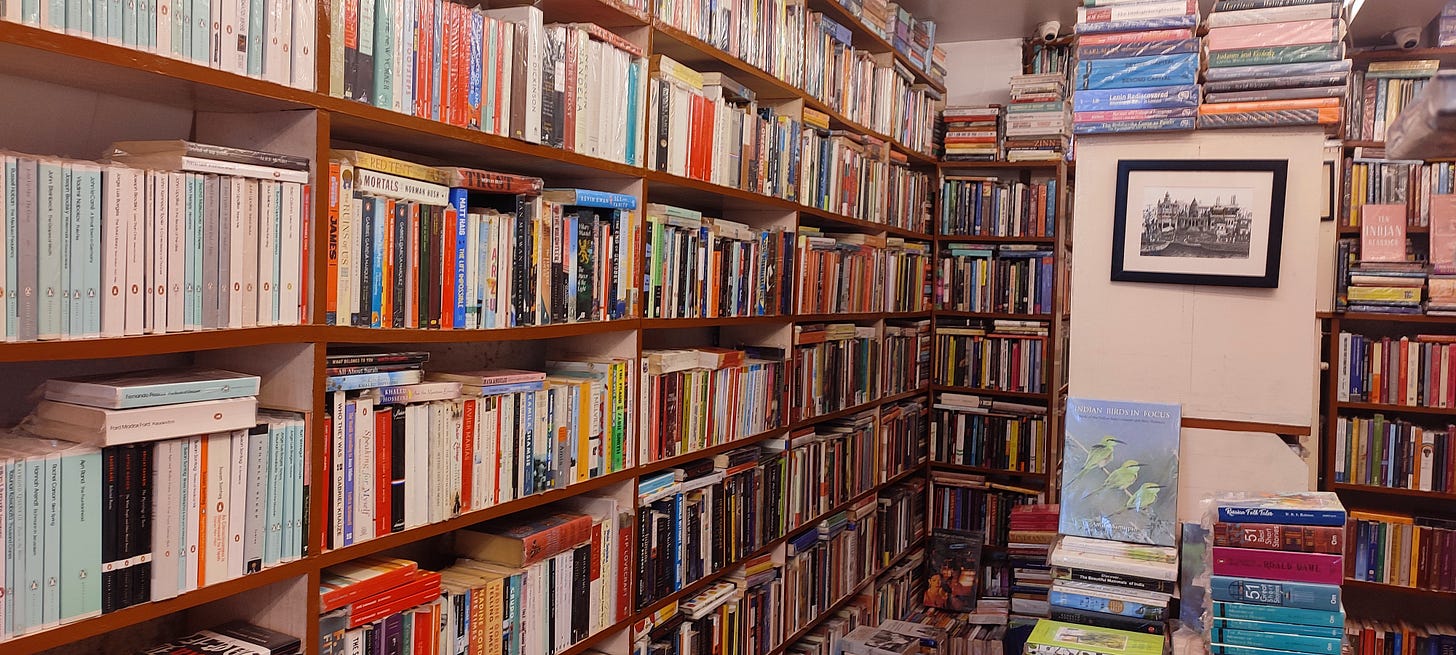

And lastly, one of my favourite finds of the tour was a small little bookstore nestled in a lane behind Assi Ghat - Harmony Bookstore, run by Rakesh Singh, who has great knowledge about the books that are housed inside his collection, and is always up for a chat about any work that captures your imagination. There were books in Hindi and English to be found on politics, philosophy, design, sociology, religion, history, art and more. I asked him for recommendations on readings on the history of Banaras, having been halfway-through City of Light at the time, and he promptly recommended “Kashi ka Itihaas” by Motichandra to me, saying that it was the most comprehensive guide to Varanasi’s history for those just getting into the subject. This book, alongside some bookmarks bought from Assi, remain the only souvenirs that I kept for myself from the trip, memories of a lifetime - my first solo trip since 2023.

I presume there must be people with a depleted attention span who could not move beyond the first few paragraphs of this article and deduce that Kashi is a terribly managed city not worth stepping foot in ever again. But not all is bad in Banaras. I would not be lying when I say that the Ghats of the city do have a certain charm to it, and while it is difficult to romanticize the dirty gullies of the inner city, I will surely find myself returning to the shores of the Ganga, to aimlessly stroll from Assi to Adi Keshava, to relish the rays of sunshine that emerge from the forests across the banks right after dawn, to take in the serenity of Lalita Ghat while enjoying a sip of lemon tea, and above all, to witness the glory of the mighty river that has carried a civilisation on her banks for millenia - a civilisation that finds its every part confluencing at the city of light.

A detailed review of all the food I had on my trip to the city is in progress, and will be released soon enough, either this Monday or Tuesday.

Most historical references and facts were taken from Diana L. Eck’s wonderful book, “Banaras: City of Light”. It is a wonderfully compiled scholarly work that I would recommend to every person interested in the history of Kashi, and for those looking for a companion to their trip to the city.

This was a very good read, I particularly didn't know a lot of little tidbits about history that you talk about. Would maybe read the book too. I am glad you enjoyed Harmony, having being from the city itself, I discovered it quite late, but occasionally I do go there, and mostly I end up buying atleast two or three books, love the varied collection